June 4, 2023

Self-reflection essential for renewing and repairing relationships

Dr. Michelle Scott concurs with the growing number of scholars who recognize the urgent need for curriculum and teaching approaches that bridge colonial divides and facilitate relational repair in Canada.

Self-reflection, she strongly believes, is a necessary but often ignored first step to achieving this goal. Such introspection can be harrowing, but it allows individuals and institutions to enter an ethical space of engagement.

“We have all been told stories about who we are in relation to our family, each other, and the ongoing history of the places we live,” says Scott, who recently completed her Doctor of Education with the Werklund School of Education and holds the roles of director of Indigenous Initiatives and assistant professor (teaching) in the Faculty of Nursing. “We need to take the time to pause to interrogate these stories through a critical lens that calls into question the colonial violence embedded in systems, policies, and stories.”

Indigenous Métissage

Of Mi’kmaw, English, and Irish lineage, she sought to understand how the ongoing legacies of colonialism had shaped her identity and how we can all become good relatives to each other, the Land and our “other-than-human kin.”

Scott was guided in her doctoral journey by three “Wisdom Guides”: Elders and Knowledge-Keepers in Moh’kins’tsis and Ktaqmkuk. This journey entailed four Vision Quests, renewing relationships with the Land by dwelling in places that held significance in her life and reconnecting with her estranged Mi’kmaw father.

Throughout her journey, she applied Dr. Dwayne Donald’s approach of Indigenous Métissage to find the stories that needed to be told.

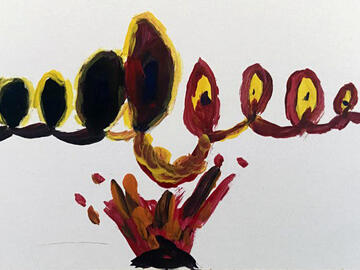

For Scott, the lessons revealed themselves through journal entries, photos, poetry and artwork. Returning to the compositions to explore their themes and through lines enabled her to weave together these separate strands of self-disclosure.

“Life writing and métissage provided a language, a feeling, a sacred space for me that felt both familiar, generative, and emergent. I was drawn to this place of inquiry as a way to self-reflect and (re)search my own complex stories of longing and (not) belongingness.”

Michelle Scott receives an eagle feather, medallion, and Pendleton blanket from Elders during the UCalgary Indigenous graduation celebration.

Colonial Shrapnel

During her creative weaving, Scott came to conceptualize colonial shrapnel. Colonial shrapnel, she explains, is the colonial violence that is embedded within our bodies through generations of spiritual, emotional and blood and bone memory. It serves to keep us wounded and apart.

“I believe that within the violent framework of settler colonialism in Canada, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples suffer affects of colonial shrapnel, albeit in vastly different ways, at different times through history.”

Tracing colonial violence and attending to our wounds is the first step to healing and telling new stories based in the truth of our shared histories.

“Through mapping the losses of my familial wounding, I have been able to illuminate the particular structure of the colonial shrapnel through generations in my Mi’kmaw family line. How the colonial violence and attempted erasure that was perpetrated on my Mi’kmaw ancestors through generations, manifested itself in interpersonal dysfunction: betrayal, alcoholism, mistrust, abandonment and spiritual dissonance.”

Elemental Kinship

If colonial shrapnel is the wound, elemental kinship is the healing balm.

Scott was again inspired by Donald’s work and his belief that we must seek understanding from knowledge systems that express alternative ways of being in order to tackle the many challenges the world faces. By turning to nature, she found her alternative system in the elements – rather, the elements found her.

She says that fire, water, earth and air contain sacred teachings passed down through the generations and offer life-giving medicine. Entering into a direct relationship with them – elemental kinship – is a pathway to healing.

“The elementals have stories to tell each of us if we sit and listen to their wisdom.”

While she received wisdom from all the elements, Scott says fire – puktew – was at the centre of her curriculum of remembering. “Each time I closed my eyes and imagined my ancestors, there is a fire, and my Pop Paul is sitting at it whittling a stick, waiting for me to arrive.”

Indigenizing curriculum

Scott is leading the development of a new nursing Indigenous Health Course.

She plans to include colonial shrapnel and elemental kinship in the course teachings as they will provide students with opportunities to gain insight through an Indigenous worldview and attend to curricular questions that operate outside of the knowledge-seeking Western educative framework.

“I envision elemental kinship as one way to seek wisdom through moving past the accumulation of knowledge – which has been enacted as epistemic violence to Indigenous peoples, and many others. I also see elemental kinship as a self-care tool which can be introduced to student-nurses early on – something that they can nurture and take up in their practice.”

Scott says ensuring that Indigenous students, faculty and staff feel that they are being heard and have a home in the Faculty of Nursing is essential, as are the ties she is making.

“To me, the success of my work is illustrated through my relationships – am I a trusted community member in my home community, in the Calgary Indigenous community, within the university, in my new faculty?”